Tel Aviv – (BBC)

The world celebrates International Nurses Day on May 12 every year in recognition of the tireless and invaluable contributions of nurses to healthcare and global health security. This celebration comes on the anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale, who is considered the pioneer of modern nursing.

Who is Florence Nightingale?

Florence Nightingale was born on May 12, 1820 in Florence, Italy and died on August 13, 1910 in the British capital, London. She was a British nurse, social worker, and pioneer of modern nursing. She also practiced statistics. This is according to the Encyclopædia Britannica.

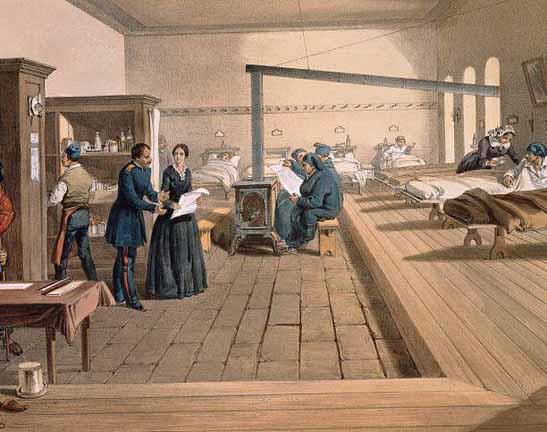

Nightingale was appointed responsible for the care of British and Allied soldiers in Turkey during the Crimean War, where she spent long hours in the wards, and her nightly rounds providing personal care to the wounded established her image as the “Lady of the Lamp” as she walked among the wounded, caring for them while carrying a lamp.

Her efforts to formalize nursing education led to the establishment of the first science-based nursing school, the Nightingale School of Nursing, at St Thomas’ Hospital in London, which opened in 1860. She was the first woman to receive the Order of Merit in 1907.

Family and the “Call of God”

Florence Nightingale was the second daughter of William Edward and Frances Nightingale. (William Edward’s original surname was Shore; he changed his name to Nightingale after inheriting his great-uncle’s estate in 1815.)

Florence was named after the city in Italy where she was born. After returning to England in 1821, the family lived a comfortable life, dividing their time between two homes, one in Derbyshire, located in central England, and the second in warmer Hampshire, located in south-central England. Their house in Hampshire, a large and comfortable estate, became the main family residence.

Florence was an intellectually promising child and her father took a special interest in her education, guiding her through history, philosophy and literature. She excelled in mathematics and languages and was able to read and write in French, German, Italian, Greek and Latin at an early age. She was never satisfied with the traditional female skills of managing a household. She preferred to read prominent philosophers and engage in serious political and social discourse with her father.

At the age of sixteen, she felt called by God to work to alleviate human suffering, and nursing seemed to be the right path for her to serve God and humanity. However, her attempts to gain training as a nurse were discouraged by her family as an inappropriate activity for a woman of her status and left her to care for sick relatives and tenants on the family estate.

In peace and war

Despite family reservations, Nightingale was eventually able to attend the Protestant Deaconess Institute in Kaisersfurth, Germany, for two weeks of training in July 1850 and again for three months in July 1851. There she learned basic nursing skills, the importance of patient monitoring, and the value of organization. Good for the hospital.

In 1853, Nightingale sought freedom from her family environment and considered becoming a superintendent of nurses at King’s College Hospital in London. However, it was politics, not nursing experience, that determined her next move.

In October 1853, the Ottoman Empire declared war on Russia, following a series of disputes over the holy sites of Jerusalem and Russian demands for protection over the Orthodox subjects of the Ottoman Sultan.

The British and French, Türkiye’s allies, sought to curb Russian expansion. The majority of the Crimean War was fought in the Crimean Peninsula, which belonged to Russia at the time of the war. However, a British troop base and hospitals were established to care for sick and wounded soldiers at Scutari across the Bosphorus from Istanbul.

British journalist William Howard Russell, the first modern war correspondent, covered the care of the wounded for the London Times. Newspaper reports stated that the soldiers were treated by an incompetent and ineffective medical facility and that most basic supplies were not available. These reports provoked the British public, which protested the treatment of the soldiers and demanded improvement of their conditions.

Sidney Herbert, the British War Secretary, wrote to Nightingale asking her to lead a group of nurses to Scutari. Nightingale led an officially sanctioned group of 38 women, departing on 21 October 1854, and arriving in Scutari at Barracks Hospital on 5 November.

Nightingale was not welcomed by medical officials, and found the conditions around the wounded to be filthy, supplies insufficient, staff unhelpful, and severe overcrowding. Five days after its arrival in Scutari, the Battle of Balaclava took place, then the Battle of Inkerman, and the wounded invaded the hospital.

In order to properly care for the soldiers, it was necessary to have adequate supplies. Nightingale purchased equipment with money provided by the London Times, and the wards were cleaned and basic care was provided by nurses.

Most importantly, Nightingale established standards of care, requiring basic necessities such as bathing, clean clothing and bandages, and adequate food. Psychological needs were taken care of by helping to write letters to relatives and by providing educational and recreational activities.

Nightingale herself would roam the wards at night offering support to patients, earning her the nickname “Lady of the Lamp”. I have gained the respect of soldiers and the medical establishment alike. Her achievements in providing care and reducing the mortality rate to about 2 percent made her famous in England through the press and soldiers’ letters.

In May 1855, Nightingale began the first of many trips to the Crimea, however, shortly after her arrival, she fell ill with “Crimean fever” and most likely brucellosis, which she may have contracted from drinking contaminated milk. Nightingale experienced a slow recovery, as no effective treatment was available, and the residual effects of the disease lasted for 25 years, often resulting in her being confined to bed with severe chronic pain.

On March 30, 1856, the Treaty of Paris ended the Crimean War. She returned home to Derbyshire on August 7, 1856.

Statistics

With the support of Queen Victoria, who invited her to meet her at Balmoral Castle in Scotland, Nightingale helped establish a Royal Commission into Army Health in 1857. She employed the two leading statisticians of the day, William Farr and John Sutherland, to analyze army mortality data. This is according to History.com.

What they found was shocking: 16,000 of the 18,000 deaths were due to preventable diseases, not battles.

Instead of lists or tables, she represented the death toll in a revolutionary way in which her “pink digram” showed a sharp decline in the number of deaths. The chart was easy to understand and made complex data accessible to everyone, inspiring new standards for sanitation in the military and beyond and public understanding of the military’s failings and urgent need for change.

In light of her work, new departments of medicine, health sciences, and statistics were created in the military to improve health care. Nightingale became the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society and was appointed an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

Health care for all

Florence Nightingale was ill but wealthy, and could afford private health care. But she knew that most people in Victorian Britain could not do the same.

Hence the poor could only care for each other. Her notes on nursing aimed to educate people on ways to care for sick relatives and neighbors, but she still sought to help the poorest people in society and sent trained nurses to homes to help treat those in need. This attempt to make medical care readily available to everyone, regardless of class or income, was an early precursor to the National Health Service in Britain.

Nightingale has been involved in working to improve the health of British forces in India since her experience at Scutari.

By the 1880s, scientific knowledge had advanced to further support her reformist ideas as she emphasized the need for an uncontaminated water supply for the people of India. As she continued to collect data, she campaigned for famine relief and improved sanitary conditions to combat the high death toll which she believed was caused by conditions similar to those she had witnessed at Scutari. Nightingale continued to receive reports on conditions in India until 1906.

She loved cats and also had a pet owl named Athena. Nightingale died on August 13, 1910 in the British capital, London.

ظهرت في الأصل على www.masrawy.com